|

WAR SERVICE RECORD |

|

|

|

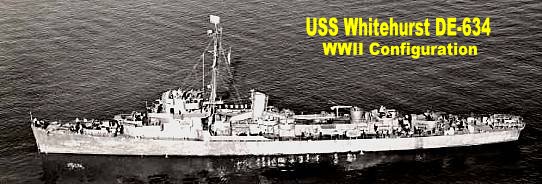

About four years ago (in fact, on New Year's Day, 1942), I returned from a gay party at the Houston Country Club given to the lawyers in the firm to my humble quarters at the Y.M.C.A. Lo and behold! The Navy had been kind enough to send me a New Year's Day present-my orders to active duty at USNR Midshipmen School, New York City. I had joined the Naval Reserve as an apprentice seaman in September, 1941, and did not expect to be called to duty until the spring of 1942. However, the attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941, doubtlessly was the compelling reason for my early call to duty. I left the firm during the first week in January, 1942, and visited in Fort Worth and Austin. While in the latter city I received new orders to report to Midshipmen School at Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois, and there I reported for duty on January 22, 1942. In one day's time I was transformed from a reluctant civilian to an eager apprentice seaman. Yes, I looked funny in my thirteen-button bell-bottom trousers, middy blouse, and sailor hat. Incidentally, the hats that apprentice seamen wear at Midshipmen Schools are ringed with a blue border to distinguish them from the regular apprentice seamen of the Navy, and there was always some ugly "scuttlebutt" disseminated to the effect that the blue-bordered hat worn by the apprentice seamen was a distinguishing mark to indicate a carrier of venereal disease. Some joke! My stay at the Midshipmen School was enjoyable despite the arduous drills, study, discipline, etc. In my company of 120 men, 38 were from Texas and about 12 were graduates of the University of Texas Law School. So I found and made many friends while there. Out of 853 graduates of my class, 138 of them were Texans. (You can see who won the war.) I discovered in Chicago a city that certainly had a heart for us service men. Its Service Center, administered by Mayor and Mrs. Kelley, was unexcelled for the generosity and hospitality which it rendered the boys. Major league baseball games, Big Ten football, bowling, ice-skating, basketball games, and other forms of sports and entertainment were free to the service men. This writer took advantage of all such opportunities. I finished third highest in my class of 853 midshipmen and first in seamanship. For the latter honor I was awarded a beautiful Navy sword at graduation exercises which took place on April 14, 1942, and was also commissioned as an Ensign in the United States Naval Reserve. I was ordered to duty as an instructor in the seamanship department at Northwestern. The only seamanship which I knew was the academic knowledge I had absorbed in Midshipmen School. In my qualification questionnaire I had stated that I had worked on a shrimp boat in Corpus Christi Bay for one summer. No doubt this qualified me as a teacher of the nautical art of seamanship. My first students at Northwestern consisted of newly commissioned officers from the civilian ranks sent there to be indoctrinated by experts (?) like myself. Needless to say, I was literally scared to death when I started teaching the rudiments of seamanship to a group of men outranking me (they were Lieutenants (j.g.) and Lieutenants) and who were several years older than I. Somehow I managed to get by for the simple reason that the head of the seamanship department was a very salty seaman; and I retold to my class the wild sea tales that he related to us, thereby putting up some sort of a front and making them think I was a salty dog, too. On June 13, 1942, I returned to Austin, Texas, to marry my law school sweetheart, then Miss Kathryn Spence, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. C. H. Spence. Kathryn was a graduate of the university of Texas, 1938, and was the Queen of the Texas Relays of that year, and was a member of the Society of Phi Beta Kappa. After a short honeymoon in San Antonio we returned to Chicago where I resumed instructing at the Midshipman School. MIAMI, FLORIDA I applied for sea duty in January, 1943, and received orders to report to the Sub-Chaser Training Center, Miami, Florida. Once again I was subjected to the life of a student, and I had to burn the midnight oil on many occasions. Some of our instructions were practical in that we did put to sea on small sub-chasers and various patrol craft. On the side, my "off" hours were delightfully spent in swimming on the famous Miami Beach, playing tennis, fishing and enjoying the usual sports that Miami tourists participate in. I finished first in my class at Miami and was again offered an instructorship in seamanship, which I declined because I felt it was my turn to go to sea and to justify wearing the star on my sleeve. I considered myself fortunate to have as much wonderful shore duty as I had. I was then offered a job as Executive Officer on a 110-foot sub-chaser. At that time the Destroyer Escorts had just begun to come off the ways and I had my mind set to have duty on this newest answer to the submarine menace. I succeeded in convincing the High Command in Miami that I should be assigned duty on a destroyer escort, and I was reassigned to a nucleus crew of one being built in San Francisco as First Lieutenant and Damage Control Officer. NORFOLK VIRGINIA In September of 1943 I received orders to report to the Norfolk Naval Base, Virginia, for duty at the Fire Fighting School. This was a necessary part of my training as a First Lieutenant and Damage Control Officer. What an experience that was! We students of the fire-fighting gang put on the regular fireman's uniform and actually fought oil fires, mattress fires, gasoline fires, etc., under simulated shipboard conditions. We did not stand around and watch the other fellows do it, because it was mandatory that all of us become actual firemen. The techniques of fighting shipboard fires were taught to us by experienced personnel who really knew how to "eat smoke." Kathryn and I managed to get a room at the famous Hotel Chamberlain on Old Point Comfort, Virginia, located across the bay from Norfolk. On one of my off days we managed to visit Williamsburg, Virginia, the original capital of that state, which partly has been restored in many respects (that is the buildings) to that of the early colonial period. The quaint shops, churches, schools, etc., had been reconstructed to conform to their original appearances. PHILADELPHIA In October, 1943, I was ordered to report to the Damage Control School, Philadelphia, for a three weeks course. Again I became a student and had to bone through such things as buoyancy, initial stability, metacentric height, shoring up bulkheads, etc. This time I finished fourth in my class. In late October I received orders to report to San Francisco for duty in connection with the fitting out and commissioning of the USS. Whitehurst (DUE. 634). SAN FRANCISCO I reported to the Superintendent of Shipbuilding, Bethlehem Steel Company Shipyards, on October 27, 1943. There began the busiest period of my naval career. I had to study the blueprints and plans of the ship, draw up various bills and drills, and check all the necessary supplies and equipment that go aboard a new ship. November 19. 1943, marked the commissioning of the USS. Whitehurst. Our ship was named after Ensign Whitehurst, a young naval hero, who was killed aboard the Cruiser Astoria during the battle of Savo Island. We made speed runs, test-fired our guns, and made calibration tests on radio and radar equipment in San Francisco Bay, and, after being O.K.'d by the Trial Board, we set sail for the warm waters off Southern California for our shakedown cruise. SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA We set sail from San Francisco under adverse weather conditions, but no mention was made to us by the Weather Bureau or by sailing authorities of a storm which we encountered about 200 miles from our destination. The barometer dropped a whole figure, the rains came, and the winds blew up to 120 knots. Compared with the severe typhoon at Okinawa last October, 1945, this 120-knot wind may have seemed like a light zephyr; but to us green sailors aboard the Whitehurst it seemed as if we were going to founder. We were tossed around like dice at the Balinese Room, but strangely enough the good old Whitehurst came through without a single leak. We lost a lot of rigging, our motor whale-boat, some depth charges and depth-charge arbors, etc., but the hull was intact. Our destroyer escort certainly proved itself seaworthy. Once at San Diego we were greeted with an arrival inspection by the local Admiral and staff. I had the officer-of-the-deck duty when the two-starred officer came aboard and I immediately started the Whitehurst off with a bang by addressing the Admiral with "Good morning, Captain!" Was my face red? The shakedown cruise was interesting but not worth describing at length. We made the usual anti-submarine attacks on tame submarines, fired anti-aircraft practices, steamed through formation maneuvers, and practiced all the various shipboard drills which would make us a fighting unit. Christmas Day came and Kathryn and I had our little tree in the U.S. Grant Hotel. Shortly after New Year's Day we completed our shakedown training, and having been pronounced fit for Jap hunting we sailed back to San Francisco, where we underwent three weeks of repair work and made preparations to sail overseas. PEARL HARBOR On January 29, 1944, I bid my wife a sad farewell and the USS. Whitehurst steamed under the Golden Gate for Pearl Harbor, Oahu. We proceeded singly and arrived without incident. Things were rather quiet at Pearl Harbor, because the fleet was out. When I say "out," I should say "in" the amphibious assault on the Marshall Island group which occurred in early February. We were in Pearl Harbor for only two days, and on my liberty day I visited Honolulu and saw the usual sights, such as Waikiki Beach, Royal Hawaiian Hotel, the "Pali," Kailua Beach, etc. Mr. Ben White's memoirs describe in detail his stay on the Island, and I will leave his description to satisfy your thirst for knowledge of that fabulous Island. Personally, I'll take Rockport, Texas. On February 7, we received orders to sail with the USS. Prairie, a destroyer tender, to Majuro Atoll, Marshalls. The Marshall invasion was only a few days old, and we all became excited with the prospect of seeing some action. At that time the fighting was still going on at Kwajalien and Eniwetok Islands. Nothing had been said in the action reports about Majro Atoll; therefore, the element of the unknown naturally aroused our curiosity as to what might happen. Well, I am glad to say that nothing did happen. Our voyage to Majuro took us about seven days. When we arrived we saw a part of the giant task force of battleships, cruisers, destroyers and carriers which had been, and was still participating in, bombarding or bombing such enemy-held strongholds as Wotje, Jaliut and Mili, none of which was too many miles from Majuro. Here was my first sight of a large naval force and it was awe-inspiring to witness our mighty fleet. After refueling we learned by dispatch that our ship had been assigned to Admiral Bull Halsey's South Pacific Fleet Headquarters at New Caledonia. We were ordered to proceed independently to Funa Futi, Ellice Islands, to pick up a convoy. SOUTH PACIFIC En route to Funa Futi we crossed the equator, and this naturally was the occasion for the initiation of us Pollywogs by the crusty Shellbacks. There were only twenty men out of our entire ship company of 200 who had previously crossed the Line. In the preliminary ceremonies the poor Shellbacks really took a beating from the neophytes. But as time neared for the actual crossing of the line, the Shellbacks used their authority and power to initiate us properly. Some fun! Arriving at Funa Futi we discovered it was just another of the many atolls in the Pacific; that is, it consisted of a series of coral islands which were irregularly arranged in sort of an oval shape which formed a natural lagoon. This affords a natural anchorage, and without such bases in the Pacific it would have been a difficult problem of logistics to have kept our naval and army forces supplied. We escorted a convoy of transports from Funa Futi to Guadalcanal without incident. After refueling at Purvis Bay, Florida Island, east of Guadalcanal, we formed up with another convoy and proceeded to Espiritu Santo, New Hebrides. At Santo I witnessed for the first time how our Navy and Army could take over an Island and developed it into a mighty stronghold and base for future operations. From Espiritu Santo we steamed to Noumea, New Caledonia, and there we visited the French capital and reported to Bull Halsey's South Pacific Fleet Headquarters. We spent a few days enjoying the delightful climate and scenery of this provincial city before returning to Santo. At Santo we learned that we had been assigned as one of many escorts for a logistic force consisting of some dozen or so fleet tankers which were to rendezvous at sea and refuel Task Force 58, which was striking Truk, Palau, Kavieng, Rabaul, and other Jap-held bases. It was a very interesting assignment, as we had the opportunity to operate with one of the mightiest armadas yet assembled. We came within five miles of Jap-held Kavieng and we expected enemy air raids momentarily, but the task unit that we were in was the recipient of only one bombing attack, and the closest that any Jap plane came to us was about three miles. Well, we were all trigger-happy, and so we let loose several rounds of 3-inch 50-caliber shells at one lone Jap bomber that came no closer than 6000 yards to us. We experienced no submarine contacts, although we had several reports that Japanese submarines had been sighted. Our tanker task group was at sea about fifteen days, rendezvousing on numerous occasions with various task units of Task Force 58. In late March we returned to Espiritu Santo to find that we had been assigned for temporary duty with the 7th fleet, commonly known as "MacArthur's Navy." NEW GUINEA We steamed in for Milne Bay, New Guinea, and arrived on Easter Sunday. Milne Bay was at that time the main base of New Guinea operations. We never had a chance to get ashore as we had to refuel and get under way for Buna Roads, the assembly point for naval transports landing crafts and escorts, and various other ships for the impending invasion of Hollandia and Aitape. About five days before we were scheduled to jump off on the Hollandia-Aitape invasion we received an assignment to escort a fresh provision ship, the USS. Mizar, to Manus Island in the Admiralty group. During the return trip this writer experienced the worst near-miss ever. By near-miss, I do not mean bombs - I mean ships. Here is the story: We were steaming 2000 yards dead ahead of the Mizar, and during my mid-watch at 2:30 A.M., combat information center (in the Navy known as C.I.C.) informed me of a radar target dead ahead of us about thirteen miles. As all officers of the deck should do, I called the Commanding Officer by 'phone and awakened him out of a dead slumber to tell him of the radar contact. The captain said to me "Ugh!" and went back to sleep. C.I.C. called me again and said: "The target is apparently a convoy composed of several ships, heading on an opposite course to ours, speed 10 knots, distance 11 miles." Mind you, we were steaming along at twenty knots; therefore, we were closing the approaching convoy at the rate of our combined speed - thirty knots. We knew it was a friendly convoy, but a friendly convoy can be dangerous if you don't get out of the way. I called the skipper again and relayed the information that there were several ships and that there would be a collision in about twenty minutes if we did not change our course. He replied "Ugh!" and remained asleep. I called the USS. Mizar by voice radio and informed them of the situation and expected a change of course, because the commanding officer of the Mizar was the S.O.P (Senior Officer Present) and he was responsible for the safety of both ships. No reply came back from the Mizar, although they acknowledged our message. A few minutes later the report came from C.I.C. that the distance to the convoy was eight miles and there appeared to be at least twenty ships in same. I told the C.I.C. officer. Norman Duncan (a former baseball player from Michigan State University and also one of my best friends, to go into the Captain's sea cabin, forcefully wake up the skipper, and tell him to come topside or have him order a change of course. So, Mr. Duncan went into the skipper's place of rest and did everything but hit him over the head with a chair in order to wake him up. The Captain must have been slipped a "Mickey Finn," because he would only say "Ugh!" and go back to a sound state of slumber. The Captain just would no wake up enough to realize the seriousness of the situation. Of course, I knew personally what to do, that is, to change course and avoid the convoy, but then, too, we were the anti-submarine escort for the Mizar, and it was our responsibility to stick with her. I knew if I changed course without permission of the skipper of the Mizar that I personally would get into trouble; so I called the Executive Officer and informed him of the situation and he dashed madly up. Again I gave him the facts, and he said, "O.K., I'll take the conn." (This means he would take over.) By this time we were about five minutes away from the main body of the approaching convoy, and, though it was very dark, I could already see the lead escorts off our bow to port and starboard. I thought surely that the Executive Officer would give orders to change course, but he stood there silently! I shouted, "You better reverse course soon or we will have a collision!" He said to me, "You mean that we are not overtaking the convoy?" I was amazed. He had misunderstood me to say that we were "overtaking" the convoy, whereas I had said the convoy was coming at us head on! What do you think happened next? Well, the Executive Officer dashed down below to C.I.C. to look at the radar screen. By this time the dark shape of the ships ahead could be seen. I said, "Right full rudder" - I missed one ship by about 100 feet. "Left full rudder" -I missed another ship. "Right full rudder" - missed another ship; and so on and on. Charlie Trippi or Jack Crain never made a better broken-field run than the Whitehurst did under the orders of Jim Nance. I scattered that convoy as a hunter does a flock of geese. They were dodging me as much as I was them. Boy Howdy! I was certainly glad that we were all dodging in the right direction, for a collision would have been disastrous and would, of course, call for a general court martial. I probably would have spent the next twenty years in Portsmouth! Anyway, we managed to get through the convoy without scraping any paint off, and later on one of my lookouts told me that he had counted at least thirty-five ships in the convoy. In the meantime, the Mizar had proceeded blithely on her way without changing course. How she managed to get through the convoy I'll never know, and I don't think that she knew either. The next day after we had arrived at our destination the Commanding Officer of the Mizar signaled over for our Commanding Officer to visit him. Our skipper then first learned of the happenings of the night before. He came back to our ship and put me on the carpet and accused me of dereliction of duty in not calling him and reporting the situation. I promptly summoned Lieutenant Duncan as my witness to the contrary, and was the captain's face red when he learned that he had been called about four times and had been forcefully shaken by Lieutenant Duncan in an attempt to apprise him of the situation! So much for that incident. NEW GUINEA OPERATIONS In late April we went in with the landing craft on the invasion of Hollandia-Aitape. We were in the third echelon that arrived on the scene, and the shooting on the beachhead was almost over. Our air force and planes from the Fifth Fleet with its pre-invasion bombardment had softened up the Japes; then too, the Japes had withdrawn their troops from the Hollandia-Aitape area and had concentrated them at Wewak, which General MacArthur had strategically bypassed. A few weeks later we escorted our amphibious forces to the Waked Island-Sarmi Beachhead, a couple or so hundred miles up the coast of New Guinea. Pre-invasion Navy gunfire had knocked out the enemy's big-gun installations. After the landing craft had beached, we were assigned to an anti-submarine station which happened to be adjacent to Wadke Island. In fact, at one end of our patrol we were only about 5000 yards from the beachhead. With our binoculars we could see the fighting going on, especially the mortar fire from both sides. We were on station at Wadke Island for two consecutive nights and each night, about 2 A.M., the Jap planes would come over and lay "eggs" on the Island. One of the bombs landed about 2000 yards from us and about 500 yards from a PT boat tender. It was a "daisy-cutter" type bomb; that is, anti-personnel, and it raised havoc on board the tender, killing several sailors, but, fortunately, the flying fragments did not reach our ship as we were just out of range. The last operation in New Guinea we participated in was at Biak, a small island in the Schouten group off New Guinea (toward the Philippines); and it was necessary to capture this Island and seize control of several enemy airdromes in order to pave the way for future advances on northwest New Guinea. Again we escorted various types of landing craft to the beachhead. We arrived there with the second echelon on the day after "D-Day." Again the bigger guns of the Navy and the air force had knocked out the major shore defenses. However, the Japes had really prepared for this invasion, as they had dug in and they also had some armored tanks. The Jap anti-tank guns gave our armored columns a fit. The enemy air force was persistent in attempting to repel our beachhead forces and they frequently came over, even in the daytime, dropping bombs on our troops. Every now & then they would make a run on a destroyer or one of our other vessels in the near vicinity. We witnessed many dog fights and saw a lot of planes shot down on both sides, but numerically we were superior, and the air battle was soon settled. At nighttime, however, their bombers would continue to drop their loads on the beachhead. One of the most dangerous, and yet ridiculous, situations that we ever got into occurred during this Biak invasion. While we were patrolling for Jap submarines off the beachhead, we observed an LCI about two miles away being fired upon by a shore battery, which apparently was so well camouflaged that it escaped detection. The LCI shouted over the voice radio, "Help! Help! Any Wolf, any Wolf, come help me!" (Any Wolf meant any destroyer in code.) Now, the biggest gun that this LCI was carrying was a 40-millimeter anti-aircraft gun. Well, we were the closest ship to her, so we dashed madly over to her assistance. When we were about 4000 yards from the point where we could see the smoke of the enemy's guns, the Japes opened fire on us and we found that we were caught in a perfect salvo of a five-inch shore battery. A perfect salvo in Navy gunfire means that the shots fall in front, in back, and on both sides of the target. In other words, the Jap shells just did not happen to "dot the 'i'" although they made a perfect, that is, theoretical, "bull's-eye." About the time our Commanding Officer gave word to our Fire Control Officer to open fire we received a message from the Fire Control Officer on the beach instructing us not to fire because our troops were encircling the enemy gun position. Much to our disappointment the Captain gave orders to reverse course, and we got the devil out of there with the Japes throwing five-inch shells at us. How in the world they missed us we shall never know; we were just plain lucky! Well, to make the story short, our troops failed to knock out the Jap gun position, and later on one of our destroyers was called upon to stand off and knock the daylights out of the Japes. After the Biak invasion we were ordered to Guadalcanal to have an overhaul; and in August, 1944, we reported to the Commander, Naval Forces, Northern Solomons, for duty. We were based at a beautiful little island called Treasury Island, which lies about sixty miles south of Cape Torokina, Bougainville. From there we made various runs to the Southern Solomons, New Hebrides, New Guinea, etc. Several times we were sent out to search for reported enemy submarines, but we did not have much luck finding them, so we had to be content with sinking or exploding a few drifting mines - some Japanese - some our own. PHILIPPINE ISLANDS (Leyte Gulf Invasion) In early October we received orders to report to Hollandia, New Guinea. We knew that the Philippine invasion was about to begin, and naturally we were all excited. All during the year 1944 the South Pacific battle cry had been "Christmas Dinner in Manila." Palau and Morotai Islands had been captured, and now we knew we were in a position to strike the Philippines. Most of us believed that we would attack Mindanao, the southernmost Island, and were quite surprised to learn that our beachhead was to be Leyte, an Island which was situated practically right in the middle of the proverbial "lion's den." But again, General MacArthur had out-foxed the Nips by not attacking where they expected us to. On October 12, 1944, we set sail with a task unit composed of eight tankers, two ammunition ships and five escorts. Again our job was to escort a logistics group whose job would be to refuel and replenish the "Fleet." We arrived off the eastern coast of Samar Island in about six days and proceeded to make rendezvous with the various task units and give them their quota of "black gold." During this period we did not sight any Jap planes, ships or submarines. On October 21, 1944, a couple of days after D-Day, our task unit entered Leyte Gulf. For the first time I saw the vast number of ships that were involved in this large-scale amphibious invasion. Attack transports, attack cargo ships, LSTs, LSMs, LCTs, tankers, provision ships, destroyers, cruisers, battleships, etc.- about 1600 vessels. The reason that our task unit was ordered to Leyte Gulf was to permit our tankers and ammunition ships to anchor and, by so doing, more ships could be refueled and replenished with ammunition than by the slower method of doing it under way. Well, every time our ships anchored, the "red" condition would be set, which meant "general quarters" for us and that Jap airplanes were on their way. The tanker unit would up anchor, get under way, and everybody would make as much smoke as possible to conceal our movements. We were attacked several times and one of our tankers received a "fish" (torpedo), but it wasn't fatal. We fired several times at attacking planes, but we never received credit for knocking any down. It was on the early morning of October 25, 1944, that one of the most interesting and decisive engagements of the war took place. It found us in Leyte Gulf, about fifteen miles from our battle line that formed in Southern Surigao Straits to meet a Jap task force coming from the west. We witnessed this night battle from our flying bridge and heard all of the battle orders, battle reports, etc., that came over the voice radio. The sky looked like a fireworks exhibition at the State Fair Park in Dallas. We had not been permitted to keep a diary or to make any notes about the war, but I did upon this occasion write down in summary form the dispatch reports of the famous battle of Surigao Straits and the second battle of the Philippine Sea. Here it is in brief form: On the 20th and 21st of October submarines of the Seventh Fleet made contact with two separate enemy forces which were later to become the Southern Attack Force and the Northern Attack Force. All during the days preceding the actual engagements these forces were under constant surveillance by submarine and carrier aircraft. The Southern Force was reported in the Sulu Sea and consisted of two battleships, two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers and ten destroyers. The Northern Force was first sighted in the Mindoro Straits and originally consisted of two heavy aircraft carriers, two medium aircraft carriers, four battleships, seven heavy cruisers, two light cruisers and twelve destroyers. On the morning of the 24th, Third Fleet carriers and cruisers were sent to intercept the Jap carrier group. The Lexington, Wasp and Hornet were on this raid. We found the carriers minus their planes, which had been sent to refuel ashore, and in the resulting fight the Japes lost one heavy and three light carriers and suffered damage to most of their heavy units, which was later to affect their fighting ability. With the damage incurred, it was believed the force would retire but they did not and jumped on through the San Bernardino Straits and out into the open sea off Samar Island. At this time heavy units of the Third Fleet were being rushed to the scene, but they were not to arrive in time. All that stood between this force and the entrance to Leyte Gulf was an escort carrier force with its destroyers and destroyer escorts. The planes of these baby carriers were sent out against the enemy within the range of her heavy guns; and, despite this fact, one heavy cruiser and one destroyer were sunk; three heavy cruisers and battleships and three destroyers probably sunk; three heavy cruisers or one battleship and one destroyer severely damaged by attacks of baby aircraft carrier planes and pursuing heavy units of Task Force 38. The enemy closed to seven miles and still could not register hits with their large caliber weapons. In this action we lost two baby aircraft carriers, two destroyers, and one destroyer escort. Meanwhile, our naval forces in Leyte Gulf were preparing to meet the Southern force. Thirty PT. boats were sent out prior to dusk to act as picket boats to report and attack enemy vessels encountered in Surigao Straits. To oppose this force we had six old-line battleships, four heavy cruisers, four light cruisers and twenty-five destroyers. These were organized into three groups, one each of cruisers and destroyers on the flanks and the battleship in the center. The enemy was sighted entering the Surigao Straits by a destroyer picket, and torpedo attacks were ordered made by a group of destroyers on either flank. Several hits were scored which slowed the enemy and at 26,000 yards our old-line battleships opened fire. The range closed to 14,000 yards, and through the combined efforts of the destroyer torpedoes and heavy naval gunfire, two battleships, one navy cruiser, one light cruiser and six destroyers of the Japanese Southern Task Force were sunk. The remaining force retired during the night and was subjected to bombing attacks by carrier planes the next morning. These attacks had to be broken off due to the approach of the Northern force off Samar, but not before the remaining heavy cruiser, light cruiser, and four destroyers could be listed as probably sunk. To quote Admiral King, Commander-in-Chief, United States Fleet: The naval action in and near the Philippines has effectively disposed of the enemy navy; a large part forever, and the remainder for some time to come. All the officers and men in the Third and Seventh Fleet have the heartfelt admiration of all men for your valor, your persistence, and success. Well done to each and all. On October 27, 1944, we put out to sea again and exited eastern Surigao Straits, and headed for a rendezvous with some baby aircraft carriers about one hundred miles off the eastern coast of Samar. Again we were with this task unit composed of tankers and ammunition ships. About 2:30 A.M., October 28, during my mid-watch, I felt the ship tremble as if from an underwater explosion that might have occurred several miles away. I reported this to the Commanding Officer and also to the task unit commander by voice radio, and we heard the same report go in from other ships in the unit. A few minutes later we picked a radar contact about fifteen miles ahead of us. A few minutes later this radar contact identified itself as being the USS. Bull, who reported that she was picking up survivors from a torpedo destroyer escort (which turned out to be the USS. Eversole), and the Commanding Officer of the Bull requested that one of our escort vessels be detached and sent over to screen him while he picked up the Eversole survivors. As our ship was the closest one to him, we were ordered to proceed to assist the Bull and to furnish anti-submarine screen for him. So we steamed off at about twenty-one knots and soon arrived at the scene where the USS. Bull directed that we take a station about 5000 yards from him and steam around in a circle gradually closing the distance to him and try to pick up the Jap submarine which we knew to be in the vicinity. What happened next can better be described by excerpts from a letter from the Commanding Officer of the USS. Bull to the Commanding Officer of our ship: The USS. Richard S. Bull requested the USS. Whitehurst to furnish anti-submarine cover to this ship while engaged in picking up survivors from the USS. Eversole, which had been torpedoed at approximately 0230, 28 October, 1944. The USS. Whitehurst reported gaining contact on the submarine and reported making several attacks. At approximately 0650, with the submarine about 4500 yards from this ship, about two small explosions which were evaluated as hedgehog explosions were distinctly heard on the sound gear of this ship. This was followed almost immediately by an extremely heavy explosion which was felt by every one aboard this ship as it distinctly jarred the ship causing the ship to rock as she was dead in the water picking up survivors. This latter explosion seemed to consist of a series of about three not quite simultaneous explosions, each of which was very heavy and gave the effect of one prolonged heavy explosion. At about 0652 the USS. Whitehurst reported her sound gear out of commission, and the USS. Richard S. Bull stood in the direction of the attack to cover the USS. Whitehurst. Contact was gained on what proved to be the explosion area at about 3000 yards. At 1900 yards, the area appeared to be about 27 degrees in width. About 100-5000 yards from this point, it was noted that a slight oil slick was beginning to form. At about 0630, the USS. Whitehurst reported her sound gear operative and back on station. This ship then returned to the survivor area to continue operations. Upon completion of picking survivors, the ship returned to the attack area, arriving at about 0810. By this time the oil slick had grown in size to cover an area about three-fourths mile by one mile, Very little debris was noted, consisting of a few rags and one piece of manila line approximately 1 1/2 fathoms in length. When this ship left the area approximately half an hour later, oil was still heavy on the windward side of the slick and showed no sign of diminishing in concentration. The oil had the appearance of being heavy diesel oil and definitely not black fuel oil. No samples were obtained by this ship as the USS. Whitehurst reported that she was doing same. Actually the Whitehurst made four runs or attacks on the enemy submarine. The hedgehog is a type of ahead-thrown projectile something like a rocket, and the launching device for the hedgehog is located on the bow of the ship. One of the main advantages of the hedgehog over the depth charge is that if the projectile fails to hit the target it will not explode, and thereby not disturb the water. It was on the fourth attack that we succeeded in hitting the Jap submarine with about seven of our hedgehogs. As we passed over her a violent explosion occurred; in fact, we thought we had been torpedoed, and our fantail (stern) was lifted practically out of the water, and various electrical equipment aboard ship was deranged and it knocked out our sound gear, equipment which is necessary to detect submarines. The weather at this time began to turn bad, a twenty-five knot wind arose, and there were huge swells in our area. Nevertheless, we put our motor whaleboat into the water, and three others and I then searched the area as best we could to recover human bodies, lumber, papers, or any evidence that would establish that we had sunk a Japanese submarine. However, the best that we could find floating around in the water were some damage-control wooden plugs, various bits of deck planking, oil samples, rags, bags of rice, and various pieces of paper with Japanese characters inscribed thereon. Parts of this evidence were sent and a full report was made to the Anti-submarine War Assessment Board, which subsequently awarded us a "B" kill which meant that we had "probably" sunk a Jap submarine, which entitles us to wear a bronze star in the Asiatic-Pacific campaign ribbon. After searching the area for about an hour, the weather became worse, so the Commanding Officer ordered the motor whaleboat to return to the ship. We rejoined our task unit several hours later and at a later date received a letter of commendation from the Task Unit Commander for our efforts. The next day we set sail for Kossol Roads, Palau, and on arriving there we learned that we had been ordered to report to the Commander of the Naval Base, Manus Island, Admiralty Group, for duty. (There I learned by mail that on my wife's birthday, October 30, 1944, the stork had presented us with a fine boy, a future Rice quarterback, Jimmy, Jr.) MANUS ISLAND We used Manus Island as a base of operations for the next three months. We made various escort trips to New Guinea, the Philippines, the Marshalls and to the Southern Solomons. During a return voyage from the Philippines with a large convoy sometime in November, 1944, we were blithely enjoying a beautiful sunny day; in fact, I was sun-bathing on the forecastle when, all of a sudden, one of our men on watch on the 3-inch 50-caliber ready gun shouted: "There are two Jap planes." There they were coming low over the horizon toward our convoy. It so happened that a task unit of baby aircraft carriers was paralleling our course about twenty miles distant, and they had dozens and dozens of "friendlies" in the air. They had been zooming over us all day, and as we were over 600 miles from the nearest Jap airplane base in the Philippines, we were never so surprised as to find two Jap planes in our midst. As we dashed madly to our battle stations, the two Japes (medium bombers) made a run at one of the LSTs, but did not drop any bombs. The two split up, one going toward the west and one to the east. The westward-bound Jap was pounced upon by two of our fighter planes and promptly 'splashed." The eastbound Jap disappeared over the horizon for a few seconds and then reversed his course and headed for our convoy. He came right at us, flying about 300 feet above the water, and we opened up with all guns that would bear on him. We set him afire with a volley from our 20-mm. machine guns and he fell into the water about 100 yards from the LST nearest us. He succeeded in dropping his bomb load, but they all missed their target. One could never be too sure of anything in the Pacific. You could never assume you were in safe waters. In late February, after about our tenth request, we were lucky enough to be sailed to Australia to rest and rehabilitate our crew. Originally we were ordered to Sydney for about ten days, but about one day out of Sydney our orders were changed and we were sent to Brisbane for only five days. There for the first time in many months we had the privilege of drinking all the sweet milk and eating all the ice cream and fresh vegetables that we could get our hands on. We found Brisbane a city of about 300,000 people whose political and economic ties were with Britain but who tried awfully hard to Americanize themselves as time permitted. They were several years behind us in fashions, methods of advertising, etc.; but the people were friendly and hospitable and were very curious to learn more about the States, and were especially interested in my native state - Texas. Clothing was strictly rationed and I was disappointed to learn that we could not purchase some of the famous Australian woolen goods. In the middle of March we returned to Manus and were promptly ordered to Ulithi, Western Carolines, for duty. OKINAWA While returning with a convoy to Ulithi from Eniwetok, Marshall Islands, we received a dispatch to report to the Commanding Officer of a task group of battleships, cruisers, and destroyers which was to be the fire support force in the bombardment of the Okinawa beachhead. We arrived in Ulithi to find that our group had left two days before. The USS. Mobile and the USS. Oakland, two cruisers, were also late arrivals, and we were assigned with three other destroyers to take them to Okinawa. "D-day" was to be Easter Sunday, April 1, 1945. We arrived on the Hagushi beachhead on March 27, 1945, to join up with our bombardment group. The big ships were steaming up and down the shoreline pouring out a volume of gunfire, and the Japs did not even attempt for fire back from the beaches. (We later learned that it was part of their strategy not to defend the beachhead.) What a thrill it was to see our vast array of forces! Our airplanes were constantly patrolling the skies overhead, and in every direction that one looked all one could see was a multitude of hundreds and hundreds of friendly ships. We all said: "This operation is going to be a cinch." The weather was exceptionally cool for us (about 60 degrees), the sun was bright, and it felt like a crisp fall-day at a football game. Well, about that time things started popping. Two Jap midget submarines were spotted by a destroyer, and you should have seen our big ships reverse course and get the heck out of there. Several destroyers made runs on the midget subs, dropped their depth charges, and we did see oil come to the surface. We never got a chance to make a run or attack on this occasion. Then the "Bettys," "Zekes" and other types of Jap aircraft came over. We saw one Kamikaze crash-dive into a cruiser through a hail of ant-aircraft fire so thick that only luck could have permitted the "heavenly wind" to get through. None attacked us and we did not fire a single shot that day. We were ordered to return to Ulithi late that afternoon, which we did, arriving there on the 29th. On the 30th we set sail again of Okinawa, this time escorting the USS. New York, a very old-line battleship. We arrived off Kerama Retto, a group of islands about twenty-five miles southwest of Okinawa. About four o'clock A.M., April 3, two days after D-day, I was summoned out of a dead slumber by the ding-dong of the general alarm to my battle station. Three aerial torpedoes went across our bow, passed astern of the New York and then exploded. Another plane dropped a load of eggs on the USS. England (DE 635) (our sister ship), but fortunately no damage resulted. We proceeded to the area due west of Okinawa where our Navy Task group was still bombarding the beaches. By this time our troops were well ashore and there were hundreds of LSTs, Navy transports, various cargo ships, etc., anchored off the beach, discharging their human cargo, guns, ammunition, food, and so on. We were soon assigned to a "picket" station patrolling off Kerama Retto, searching for submarines and also serving as an anti-aircraft screen. Kerama Retto is a group of small islands which form a natural protective anchorage and therein many of our tankers, ammunition ships, and various other supply ships were anchored. Various elements of our fleet would go in to the anchorage and go alongside these vessels to take on needed fuel, ammunition, food, etc. Our ship was just one of over a hundred or so destroyer-type vessels which formed an anti-submarine circle around the entire western side of Okinawa and also around the Kerama Retto Islands. Between the 3rd and 4th of April we were called to general quarters on numerous occasions, especially in the early morning hours, and we saw lots of Jap planes at a distance but none attacked us. We were receiving reports that quite a few of our fellow teammates on the picket line like ourselves were being attacked and were being hit by suicide planes. On April 6 things did happen. We were still patrolling off Kerama Retto, and dozens of Jap suicide planes attempted to get into the anchorage. Most of them were shot down, but I saw six of them crash-dive into our own ships and start tremendous fires. We fired at several Jap planes but did not bring any of them down. There were dog fights everywhere - we even saw one of our own awkward "Dumbos" (Navy patrol type plane) shoot down a Jap "Val" - an obsolete type of dive bomber. Most of the Jap suicide planes were coming in low over the water - about fifty feet altitude - and going straight at their target. I don't understand how the Japs could possibly miss their aim using these tactics, but they crash-dived more into the water (near misses) than they succeeded in hitting the bull's-eye. A big ammunition ship came dashing out of the Kerama Retto anchorage and signaled us to get in front of her as escort. It was an order and so we did! Were we scared! We had seen the Mount Hood, an ammunition ship, blow up at Manus from a distance of three miles, and we thought the world had come to an end. There we were only 300 yards from a huge ammunition ship - a veritable powder keg. Sure enough, a Jap twin-engine bomber - a "Betty" - came out of nowhere at dusk and made a run on us from dead ahead. Our forward guns opened up on him and we could see that our bullets hit him; nevertheless, he seemed to fly right on through our tracers. Just as we expected him to crash into the forward part of our ship, he dipped his wing and turned away and then swung toward the ammunition ship. We held our breaths, anticipating a violent explosion which would blow us all to Kingdom Come. But again the Jap pilot apparently lost his nerve and zoomed away and this time headed for a lone merchant ship setting her on fire and she later blew up. In all, over twenty-three ships were victims of the Kamikaze on that day, several ships being sunk outright, and the rest of them severely damaged and thereby put out of the operation. On the credit side of the ledger a total of over 175 Jap planes were either shot down or were their own victims by crashing into our ships. Between the 6th and 12th of April the Kamikaze attacks were sporadic and less intense; nevertheless, at least five or six ships were "picked off" daily. At nighttime we patrolled at slow speed because a faster speed would create a wake which airplanes could easily detect from the air. We could hear the Jap airplanes buzzing around us often, and truthfully, we were all very much scared. It was not wise to fire at the Jap airplanes at night without special fire-control instruments, which our ship did not possess. On April 11 about 4 P.M. we put into Kerama Retto anchorage to refuel. While taking on black oil, the Japs flew over and attacked two destroyer escorts patrolling stations numbers 23 and 24 (just outside the entrance to the Bay). Reports came in over the voice radio that both ships had been hit. When we finished refueling, we asked our boss for our station assignments for the night, and guess what we got? Yes - we were ordered to take stations number 23 and 24, which had been the "hot spot" ever since the invasion began. By "hot spot" I mean that about seven destroyer escorts had taken it on the nose by the death-dealing Kamikaze. Well, we reluctantly took our assigned stations. Several enemy raids passed over us during the night, but again we did not open fire on them, fearing that we would reveal our ship. The next day, April 12, turned out to be the red-letter day for the USS. Whitehurst. Tokyo Rose had warned us the night before that there would be an all-out air attack by the "Heavenly Winds." Admiral Turner (in charge of the invasion) sent out a dispatch warning every one to be especially alert, as his intelligence reports indicated that the Japanese were coming down from the island of Kyushu in an unprecedented raid. All knew what they were talking about, because on April 12, 1945, the suiciders came howling down with death in their hearts. About 2:30 P.M. I was writing a letter to my wife Kathryn in my stateroom when the general alarm sounded and we all dashed to our battle stations. We spotted five Jap dive bombers - recognized as "Vals" (we could see their non-retractable wheels) approaching from the west. (I was at my damage-control station amidships - inside the hull - and the Captain's talker relayed to us all the reports on the enemy.) Three of the planes peeled off the formation and proceeded to maneuver into position to attack us. One approached from our port side first and our five port-side 20 mm. machine guns and our 1.1 quad. and our 3 50-caliber main batteries began pouring out a barrage of anti-aircraft fire. While this was happening, the other two Jap suiciders came in from our starboard side and we had only five 20-mm. anti-aircraft guns to combat that secondary attack. (Actually our Captain and our Gunnery Officer never saw the two Jap planes approaching on our starboard side, as they were observing the fire of our main batteries at the port-side attacker.) Strangely enough, our five 20-mm. machine guns on the starboard side succeeded in "splashing" the two Jap planes about 200 yards away from our ship, whereas all that the main battery and the other machine guns on the port side could do was to set that attacker on fire. The port-side Kamikaze hit us in the superstructure exactly where our combat information center is located, killing instantly all men stationed there, plus all men in the pilot house just forward of C.I.C. There was a terrific gasoline explosion which was followed by a huge fire, engulfing the entire superstructure. Gasoline poured down into the radio room below C.I.C. and killed or seriously injured all men there. The plane was carrying a 500-pound delayed action bomb, which carried on through the hull and exploded on the starboard side about fifty feet away from the side of the ship. Fragments of the bomb killed or seriously injured every man on the forward guns - about thirty in all. I rushed to the scene of the fire with my fire-fighting party and in about ten minutes we had the blaze under control, though we spent over an hour putting out small fires that kept breaking out in compartments below. I had never seen the horror of death at close hand. One minute we were a crew of 189 men. The next minute, 42 were killed or missing in action and over 40 were seriously burned or injured. My roommate, Lieutenant Robert J. Purtell, Brooklyn, New York, serving as Communication Officer on Board ship, was killed in C.I.C. My best friend, Lieutenant (j.g.) Norman J Duncan, and my good friend and Executive Officer, Lieutenant Yates Bullock, of Rocky Mount, North Carolina, were missing in action and have not been heard of since. We had no doctor aboard, and the chief pharmacist's mate was severely burned and out of action, and that left a pharmacist's mate third class as the lone medical corps representative aboard. What a marvelous job he did, assisted by various members of the crew, in taking care of men who had sever abdominal wounds or who had lost arms and/or legs, etc.! It took some quick and skillful first-aid to save their lives. Several ships dashed over to lend assistance later on, but we managed to creep into Kerama Retto, in "graveyard row," under our own power. By "graveyard row" is meant that there were about twenty destroyer-type vessels which had been put out of the operation by virtue of suicide hits and had been towed in or had come in under their own power for temporary repairs before they could proceed to rear areas to get permanent repairs. Again, over twenty of our vessels had been successfully attacked by the Kamikaze, but on the other hand it is estimated that we had taken care of over 300 Japanese airplanes. We made temporary repairs in Kerama Retto, and on April 16, 1945, we joined up with a convoy of attack transports and cargo ships heading for Saipan. Our entire communication set-up (radios, radars, sound-gear, etc.) was out of commission, so we were of no use as an escort ship and were, therefore, assigned as just one of the many ships in the convoy in the rear of one of the columns. We arrived at Saipan in late April, where we received mail for the first time in six weeks and received further orders to head for Pearl Harbor, by way of Eniwetok, Marshall Islands. PEARL HARBOR AGAIN We arrived at Pearl on May 12 and learned to our great disappointment that the ship would be repaired there and not in the States. Also the ship was to be converted into a "power ship." The main propulsion on our ship was turbo-electric, and by adding some transformers and other special equipment we could generate 40,000 volts of electricity. In the meanwhile, I succeeded in obtaining thirty day's leave and I flew home all the way to Austin, Texas, in four different airplanes in the elapsed time of forty-three hours, and there for the first time I saw my six-months'-old son, Jimmy, Jr., and my wife, Kathryn, for the first time in about fifteen months. A grand reunion was had and before I knew it I was back in Pearl Harbor. After obtaining a thorough overhaul and being completely repaired, and after undergoing another shakedown cruise with a brand-new crew, we set sail for Manila, Philippine Islands, and arrived there on the day that Japan unofficially surrendered - I believe August 14, 1945. MANILA, P. I. The ship immediately began supplying power to the war-torn city of Manila. Another destroyer-escort power ship and the Whitehurst furnished about 90 per cent of the electricity that the city and the Army units stationed there consumed. I made many inspection trips about the city of Manila, explored the various native sections such as Chinatown, Spanishtown, etc. There I discovered that I had lost nothing. The Japanese had deliberately bombed or used demolition charges in blowing up every business building, hotel, or residence that they could, ruthlessly and without reason. The most interesting sights that I observed there were the Chinese cemetery, the President's palace, Chinatown, Santo Tomas College, and the University of the Philippines. On October 22 I received my going-home orders from the Commander of the Philippine Sea Frontier, and the next day I ran into my wife's brother and one of my best friends, Ralph Spence, and we joined up and came home together on the USS. Kingsbury, APA-177. HOME We arrived in San Francisco on November 17, 1945, and proceeded to the Separation Center at Camp Wallace, Texas, where I received those beautiful separation orders on November 27, 1945. I was given sixty-four days' terminal leave at Uncle Sam's expense, which was thoroughly enjoyed by me. January 2, 1946, found me back in the saddle with Baker, Botts, Andrews & Wharton, and my first assignment was writing my War Service Record. Here it is, and may God grant that there never be a future occasion for me to write another war record.

|

WWII

Era | Korea War &

'50s | Viet Nam & 60s |

Reunions |

All Links Page

Search & Rescue

Memorial | Poetry | Enemy Below | Taps List | Photos/Armament | History | Crews Index | Home