|

|

| Excerpts from

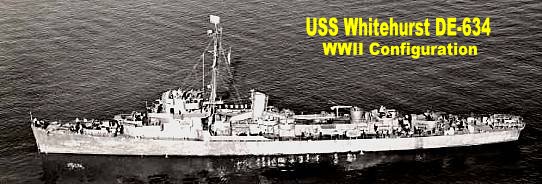

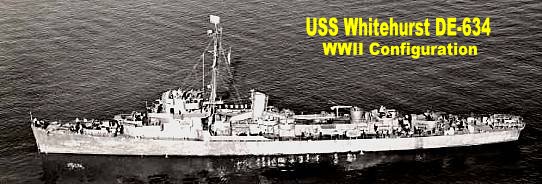

"Tempest, Fire and Foe" by Lewis M. Andrews Jr. Eversole - Whitehurst - Bull Disaster and Victory, Pages 174 & 175 9 August 1944. Eversole (DE-404) put to sea, screening carriers for the attack on Morotai. She continued serving with escort carriers in the initial assaults in Leyte Gulf on 20 October. Eversole's orders on 27 October were to rendezvous at daybreak the following morning with Rear Admiral Sprague's battered Task Force (Taffy 3), returning from the Battle off Samar. 0210 on 28 October. The DE made a radar contact at 5-1/2 miles that then disappeared. Within eight minutes, the sonar watch advised the conn that they were echo ranging on a contact at 2800 yards. A half minute later, a torpedo crashed into the ship, causing immediate loss of power and a 15 degree list. Within seconds, another torpedo found its mark through the same gaping hole ripped by the first one. The explosions wreaked havoc below decks, mortally damaging the ship and rapidly increasing her list to 30 degrees. Dead and wounded were everywhere. With damage control unable to cope with the immensity of the destruction, the commanding officer, Lieutenant Commander George Marix, ordered the ship abandoned. Within 15 minutes, Eversole plunged to the bottom. Captain Marix recalled: "I was on my way to the bridge when the first torpedo hit. A second Torpedo hit shortly afterward, but no panic was noticed in the abandon ship procedure. I made a personal inspection of the ship as far as I could. Three men were frozen to the rail, afraid to move. I beat their fingers until they dropped into the water below. On my final check, I found a man with a broken leg. I lowered him into the water with a line attached and then followed him in because the ship was flat on her side and I thought it was time to leave. After stepping into the water, I towed the injured man to a floater net about 100 yards away. On the way, I picked up a life preserver as I had given mine to the wounded man." The men scrambled over the side as best they could, taking the injured with them. The Captain continued: "There was another floater net about a hundred yards away. I ordered them lashed together so as to concentrate the men. Officers were placed around nets 10 yards out to pick up any who might slip off and drift away. 0300. A submarine surfaced near a group of men hanging on to a raft some 200 yards away from myself. Some of the survivors, unable to identify the sub through the predawn gloom and believing that a friendly ship had come to their rescue, shouted loudly. Their pleas were answered by a murderous and ruthless hail of 20mm fire from the Jap sub that lasted for 20 minutes. Fortunately, it was so dark and raining that their gunner couldn't see us, and nobody was hit. The men were ordered to keep quiet as the sub circled us about 150 yards away. After 20 minutes in our area, the sub submerged, followed five minutes later by a terrific underwater explosion that killed or injured many survivors in the water. My communications officer, about five feet from me, was killed instantly. I was seized with very bad cramps and lost all control of my bowels. Unconscious men began drifting from the floater net. My officers, aided by some slightly injured men and myself, swam them back to the net and put them aboard. I estimate that this explosion killed about 30 men. The detonation was believed to have been caused by a time-set anti-personnel bomb. It could not possibly have been one of our depth charges because they had been set on safe and because a half hour had elapsed since our ship went down." Bull (DE-402) had arrived in an area of heavy oil slicks and survivors in the early morning of the 20th. Quartermaster Third Class Robert L. Smock had unforgettable recollections of the rescue: "It was very late at night when we lost the Eversole from our radar screen. Needless to say, we came across the crew in the water. I can vividly remember the smell of the fuel and hear those cries for help. It is a cry like none other in the world!" Captain Marix concluded: "At about 0400, we sighted Bull and attracted her attention by means of flashlights. She circled us for about an hour until Whitehurst (DE-634) arrived on the scene to act as covering ship. While circling the area, Bull frequently stopped to pick up survivors. By 0630, all survivors had been taken aboard. I wish to commend all my officers and men for the fine work they did in spite of their own injuries. The torpedoing and the bomb created unusually high casualties. Out of a roster of 213 officers and men, 77 were dead and 136 were rescued, all injured. Of the latter number, three subsequently died, bringing the death toll to 80. Had it not been for the arrival of Bull and Whitehurst shortly after sinking, the death toll would have been total. The efforts of the officers and the men of the Bull in recovering and caring for my crew were exemplary. The doctor on board, Lieutenant Hartley, from the oiler Sangamon (AO-28), undoubtedly saved the lives of some 30-40 men by his untiring efforts and skill. He worked without rest for 36 hours, treating the critically wounded." Having exhausted her supply of blood plasma, Bull acquired an additional supply from Whitehurst. The officers and crew worked day and night trying to relieve the sufferings and save the lives of many of the badly burned members of the Eversol. Prior to the submarine attack, and after fighting off two attacking planes on 27 October, Whitehurst proceeded to a rendezvous east of Leyte Gulf. She had been acting as escort for Task Unit 77.7.1 during fueling operations at sea and in Leyte Gulf. During the night of 28-29 October, the Task Unit had been steaming slowly to await daylight and continue fueling ships. Submarines had been reported in the area, and it could be presumed that the Japanese were by this time aware of the routes used from Hollandia to Leyte Gulf. 0325. A strong Underwater explosion had been heard on Whitehurst, judged to be several miles away. The weather was cloudy, obscuring the moon, and with occasional rain squalls reducing visibility. The breeze was light and variable with calm seas and a long, low swell. Word was received from Bull that the Eversole had just been sunk and Bull was requesting an escort to act as an antisubmarine screen while she was rescuing survivors. The Screen Commander on Bowers (DE-637) detailed Whitehurst to be the screening vessel. The DE's speed was increased to full and a course was set for Bull. CTU 7.7.1 ordered the convoy on an emergency turn to reverse course and to clear the danger area. Eleven minutes later, Whitehurst had closed the range to Bull to three miles. The range and bearing to the center of the survivor area from the Bull was determined and plotted on Whitehurst's DRT. Because of poor visibility and on the advice of the Bull, speed was reduced to 10 knots in order not to run down any survivors. Operation Observant was begun, using beam to beam sonar search. At 0515, visibility had improved, and speed was increased to 18 knots, then considered to be the maximum speed at which a good search could be made. 0545. After nearly completing an entire search around the area, Whitehurst made a good sound contact and slowed to 10 knots for attacking with hedgehogs. Three attacks were made over the next 90 minutes without result. The fourth run, however, was a different story. A few seconds after the bombs hit the water, six minor explosions were heard in quick succession. In true form, there was a violent underwater detonation, followed by heavy rumbling noises! The echo ranging gear on Whitehurst was knocked out by the blast. Accordingly, Bull was asked to continue the search and to attack. Bull made a contact at the point of explosion and searched the area. However, she reported that her echo was only from the water disturbed by the explosion. Bull commented to Whitehurst over the TBS: "From the sound of the explosion where I was three miles away, I don't think there is any chance that there is anything left of the sub." 0720. The Whitehurst sound gear was repaired leaving Bull to continue the rescue of survivors. Considerable oil on the surface was noted, along with pieces of wood and other debris, but Whitehurst launched Operation Observant as a precaution. She lowered her boat in the center of the oil slick to retrieve debris. An hour later, her motor whaleboat retrieved numerous pieces of deck planking, a damage control plug with Japanese marking, other pieces of wood painted red and oil samples soaked up in rags. At 1215, the search was abandoned. The heavy underwater explosion had been of such violence that, at first, it was thought that the ship had been torpedoed . All departments reported, and the only damage was to the sound gear which was temporarily out of action, fuses having blown in the three phase power supply. The after engine room reported a lube oil pump stopped, caused by the concussion tripping a solenoid valve. The sound gear was checked out by the leading soundman and the electrician's mate, and the trouble was quickly located and repaired. The submarine was credited by her attacker for excellent evasive tactics and maneuverability. She would invariably try to turn away from the attack, presenting her stern and wake. At her depth of 225 feet at the time of losing contact, this was the best maneuver; a salvo could not be fired until after contact was lost, giving the sub additional time for evasion. At a later date, it was confirmed that Whitehurst had sunk Japanese submarine I-45, the same one that sank Eversole. Further actions with Japanese aircraft by both Bull and Whitehurst are

described in chapters The Philippine Campaign and Iwo Jima to Okinawa - The

Destroyer Escorts. |

|

Whitehurst - An Unhappy Introduction to the Kamikaze Pages 289 & 290 |

| Barely a month after sinking the Japanese submarine I-45 (See chapter

Pacific Antisubmarine Warfare), Whitehurst (DE-634) again came to grips with the

enemy on 21 November 1944 while screening a 12-ship convoy en route to

Hollandia. On each of two occasions, she was attacked by a Japanese Lilly. In

the first, attack, the plane skimmed over the water, dropped one bomb which fell

clear of the ships, caused no damage and then departed. The pilot of the second

plane was less fortunate. As he started a low, gliding bombing attack, the DE

commenced fire. Immediately afterward, other ships of the convoy opened up, and

the aircraft splashed! Whitehurst received the major credit.

23 March 1945. After a lengthy sojourn to Australia, a tonic for the crew, Whitehurst joined the armada preparing to invade Okinawa on the very doorstep of Japan. Two days later, this DE and England (DE-635) were among the first American ships to arrive. 6 April. While patrolling off Kerama Retto, Whitehurst opened fire and drove off an enemy plane that was attacking SS Pierre. Evening of 11 April. Whitehurst cleared Kerama Retto anchorage after fueling and was assigned a perimeter station relieving Manlove (DE-36). Miles (DE-183) was relieved from an adjacent station, leaving Whitehurst to patrol both sectors. Her mission was to search the area, using underwater echo-ranging gear and radar to prevent entry of submarines, torpedo boats, kamikazes or other enemy forces into the Kerama Retto anchorage. Nearby stations were manned by Vigilance (AM-324) and Crosley (APD-87). 1430. Four Vals intruded into the area at an altitude of 1500 feet. They split up to evade friendly fighters. One aircraft unsuccessfully attempted to attack Crosley. Another broke away and headed for Whitehurst where it was promptly taken under fire by her 3" guns. It circled rapidly and commenced a 40-degree angle dive. At the same time, two other Vals attacked, one from the starboard beam and from astern. The two latter planes were shot down in flames by the DE's starboard 20mm and 1.1" guns! However, the first plane continued its dive in spite of receiving several 20mm hits that tore chunks out of the plane. The kamikaze crashed into the ship's forward superstructure on the port side of the pilot house, entered the combat information center and burst into flames. A small bomb jettisoned loose, went completely through the superstructure, and exploded some 50 feet off the starboard side. Whitehurst steamed around in circles out of control. The Val had demolished the CIC immediately below the flying bridge, enveloping the entire bridge structure in a roaring fire and black smoke shooting up into the sky. All hands in the CIC and the pilot house were killed instantly as well as those in the radio room just below the CIC. All the men at the forward gun mounts were either killed or severely wounded by bomb fragments. Unharmed officers and men displayed an heroic discipline in rushing to the aid of the damage repair parties, saving the DE from total destruction. The ship was in a tight turn to the left and when it headed into the wind, the flames and smoke cleared sufficiently to enable several flying bridge personnel, including the wounded commanding officer, Lieutenant J. C. Horton, to escape over the forward side of the bridge structure. By the time the Captain made his way to secondary control, communication had been established with the engine rooms, after steering and after guns. The repair parties were already fighting the fire, and the ship was then headed across the wind to allow the flames to blow clear. When Vigilance received the message that Whitehurst had been hit and needed assistance, she rang up full speed and raced to the burning DE. By the time she arrived, however, the Whitehurst crew had the fire under control. Nonetheless, the minesweeper lent invaluable medical assistance in tending to the wounded. The prompt administering of first aid and the injection of plasma saved many lives. Of the 23 wounded men treated on the Vigilance, 21 recovered. By mid-afternoon, the fires were almost extinguished, and four men who had been blown overboard were picked up by Crosley. Since all of the signal bridge personnel on Whitehurst had been wiped out, killed or wounded, Vigilance put a signalman on board the stricken ship so that she would have a communications capability. Captain Horton concluded in his action report: "The officers and crew reacted very well to their first battle casualties. The after gun crews stood by their guns although, at first, it may have appeared that the ship was doomed. In addition to prompt assistance from Vigilance and Crosley, first aid training by the crew proved of great value. Although one third of the compliment was either killed or seriously wounded, and the leading pharmacist's mate was badly burned, all wounded were cared for quickly. It is believed those who died could not possibly have been saved." Whitehurst limped into Kerama Retto anchorage for temporary patching to make her seaworthy. Shortly there after, the battle-scarred veteran departed for Pearl Harbor to receive proper battle damage repairs as well as some up-dated alterations. This was not the end of Whitehurst. The DE, with turbo-electric

propulsion, was converted to a floating power station. On 25 July, she headed

for the Philippines. Although Japan had surrendered soon after her arrival, she

stayed to supply the city of Manila with power for the next three months.

|

|

WWII Era | Korea War & '50s | Viet Nam & 60s | Reunions | All Links Page Search & Rescue Memorial | Poetry | Enemy Below | Taps List | Photos/Armament | History | Crews Index | Home

|