|

St. Helenan remembers kamikaze hit

This article was published in the St Helena Star, Dec. 17, 2009 (St

Helena, CA)

By John Lindblom

STAFF WRITER

Thursday, December 17, 2009

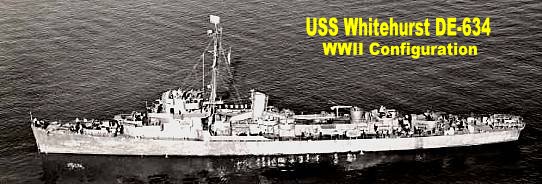

From his battle station in the forward engine room of the USS

Whitehurst, a destroyer escort, Engineering Officer Sydney Calish felt

the horrific explosion and scrambled1

topside to see what had happened.

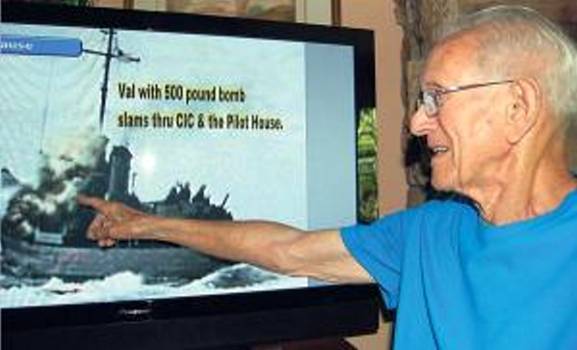

John Lindblom photo From a photo preserved on a DVD of the incident,

St. Helena’s Sydney Calish points out the Japanese kamikaze that hit

his ship, the USS Whitehurst, on April 12, 1945, on his TV screen.

Note the tail section of the plane at far left.6

One of his first observations was the helmsman, slumped but still

standing at the helm with both hands on the wheel, and his close

friend in the combat information center still stood with his arms

outstretched around two radarmen as if trying to protect them.

All were dead, as were 34 other of Calish’s shipmates. Twenty-three

more were injured — most of them seriously. Two of the 23 later died.

It was April 12, 1945 — a fateful day for Americans, as it was the day

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt died. And especially fateful for

the men of the Whitehurst, one of 21 U.S. ships hit by Japanese

kamikazes that day.

“I didn’t see the explosion. All I saw was the aftermath. Those who

were still there looked like figures in a wax museum, because a lot of

them were killed by the concussion,” Calish, a St. Helena resident,

recalled. “They were burned, too, but it was the concussion that

killed them, like being hit over the head, I guess.”

At the time, the Whitehurst was in a picket line in the waters off

Okinawa, patrolling for submarines and “Vals,” the Japanese code name2

for their kamikaze suicide planes.

For its part in the last big naval battle of World War II, Calish’s

ship had been ordered to join an attack force and had steamed in from

Ulithi naval base in the Caroline Islands.

“We were apprehensive in Okinawa,” he remembered, “because there had

been so many ships lost there. We were assigned to a radar picket

station where two ships had just been hit.”

But the Whitehurst crew knew its business. In the battle of Leyte Gulf

they had sunk a Japanese submarine (albeit unofficially because all

anyone ever saw was an oil slick and debris floating to the surface)

and were credited with downing four fighter planes.3

So when trouble from the air came in the form of four Vals, three of

them wound up at the bottom of the sea. The fourth, however, came

directly at the Whitehurst.

“It hit the port side, went all the way through the deckhouse and

wound up on the starboard side,” said Calish. “It was carrying a

500-pound armor-piercing bomb, but it didn’t hit the ship; it went on

[through the ship] and detonated in the air.”

Reflecting on the kamikazes and the pilots who flew them, he added,

“They (Japanese military) would provide only enough fuel that the

planes couldn’t get back to their home base. It was the same (logic)

as suicide bombers today. I don’t understand it, and I don’t think the

Western mind can grab hold of it.”

Calish was a member of the Whitehurst’s 210-man crew, and had an

almost familial feeling for the ship. He is a “plank owner,” and was

present at its commissioning ceremony in San Francisco in November

1943.

It was a rare fighting ship, one of only six destroyer escorts powered

by a turbo-electric engine in World War II.4

A newly minted officer, Calish was an Easterner who came west with his

family and graduated from UC Berkeley as a chemistry major in 1941.

After entering the Navy, he spent four months at the U.S. Naval

Academy in Annapolis, and learned most of what he knew about

engineering at Cornell University’s diesel school and a sub-chasing

center in Miami, Fla. He might have stayed in the Navy beyond the

three years he served, but his new bride saw what military families

endured while growing up in Long Beach and would have none of it.

Instead, Calish went to Chevron as a researcher.

The patched-up Whitehurst, meanwhile, sailed on, distinguishing itself

in the Korean War with three battle stars in less than a year. It also

played a role in the film “The Enemy Below” as a destroyer escort

under a fictional name, and survived a collision with a Norwegian

freighter that culminated in both vessels running aground.

At the ripe old age of 25 in 1969, the Whitehurst was finally

decommissioned. Two years later, the ship was torpedoed and sunk as a

target off Puget Sound.

Calish has a tattered ensign5

from the Whitehurst, and the ship’s destruction, he said, was a sad

moment for him and, doubtless, his surviving shipmates.

“I think it was,” he said. “You certainly form an attachment to the

people who served with you. I’ve been to a couple of reunions with

them. There aren’t many of us left.”

notes by Max

Crow, Webmaster USS Whitehurst Assn.

*corrections to the misleading statements identified by

numbers above.

1.

He did not leave his battle station to scramble topside. He went

topside to survey the damage after the ship was at her birth in Kerama

Retto.

2.

American Code name for the Aichi D3A, a Japanese Dive Bomber

3.

Prior to April 12, Whitehurst had downed only a twin engine bomber.

During the battle, her gunners shot down two Vals before the Suicide

strike and one after.

4.

Whitehurst was one of 6 Turbo-Electric DEs manufactured by

Bethlehem Steel. There were many other TE DEs in the war.

5.

Syd has a photo of Whitehurst’s tattered battle ensign. The actual

flag is in the possession of the Whitehurst veterans and families who

attend the reunions. It is now in a protective glass case which is

shown at every reunion.

6.

The picture displayed is from the Whitehurst WWII History DVD which I

produced from the war time log kept by George Baskin. There was

no battle photographer aboard Whitehurst or nearby when the suicide

bomber struck. The picture is a photo which has been

edited to illustrate the strike.

|