|

MEMOIRS OF

MY EXPERIENCE

WITH THE KAMIKAZE ATTACK |

|

|

|

|

|

Frederick W.

Mielke, Supply and Disbursing Officer |

|

|

|

|

|

Ensign Fred Mielke |

Fred Mielke ca 2001 |

|

I Brief Account

The kamikaze, a Val bomber, tore through

Whitehurst’s superstructure from port to starboard, coming to rest

on the starboard searchlight platform. Its 500-pound delayed-action

bomb continued on and exploded about 50 feet off the starboard bow,

with deadly effects on personnel with battle stations on deck. The

plane went completely through the CIC Room and Pilot House, killing

all there. On the deck below, in the Radio Room, where four of us

had our battle stations, the plane ripped a gash in the overhead,

sending flaming gasoline into the room and adjacent passageways.

William Yeager (RDM3c) and I were lucky enough to escape with only

burns. Irving Paul (RDM2c) was killed outright when the door of the

Radio Room slammed into him after being blown off its hinges and

into the Radio Room by the piston-like pressure of the kamikaze’s

impact into the ship’s tightly closed up superstructure. Most sadly,

True Lofton (RDM3c) died of asphyxiation trying unsuccessfully to

escape the fire and smoke by retreating from it as far as he could

(he reached the vacant Captain’s Cabin) to avoid going through a

flaming passageway to get to fresh air.

The two of us who escaped chose to

make a seemingly impossible effort to get out of the closed-up space

by dashing aft through the flaming passageway to get to the

watertight door that led outside to the boat deck. To escape, we

knew we had to survive long enough in the flames to unlatch the six

lugs (dogs) that held the massive steel door shut. This would

require unlatching each of the lugs by hand, because the door was

not one with a single central wheel that controlled all the lugs.

As it turned out, the two of us

were lucky. The same force that had blown the Radio Room door off

its hinges had been strong enough also to blow that heavy steel door

off its hinges. In the process, it had bent or broken away the six

heavy steel lugs that clamped the door shut.

It was months later, when I rejoined the ship in

Pearl Harbor after being treated for burns, that I learned the story

of the blown-away door. I had been in a quandary. I had no

recollection of actually undogging that door, yet I remembered

falling down over the coaming of that opened door and someone

scrambling over me to get out. I assumed, but could not believe, I

had actually undogged the door. I also knew, however, that I was

confused and desperate in the flames and probably not fully aware of

what was happening.

When I related this quandary to my

shipmates, I got this reply: “You know, we never did find that

door. It was completely blown away and must have gone overboard.

We looked for it everywhere.”

So there was the answer. It fitted

my memory. I knew there was no way we could have undogged that door

before succumbing to the heat, flame and smoke. We were lucky.

II More Details

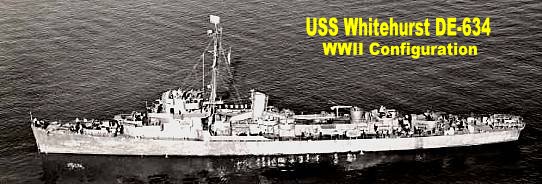

On April 12, 1945, during the

Okinawa campaign, Whitehurst was attacked simultaneously by three

kamikazes in mid-afternoon (about 1500). One, approaching from the

starboard beam, was brought under fire by the ship’s four starboard

20-mm automatic guns. Another, approaching from the stern, was

fired upon by the ship’s two aft 20 mm automatic guns, its single

1.l inch automatic gun, and its aft 3”/50 caliber gun. Both planes

crashed in flames nearby.

The third plane, more distant, was

fired upon as it came within range. Two friendly fighters were also

attacking it from above, but these veered away from the gunfire.

The plane started its dive of about 40 degrees off the port beam.

It was hit with several 20-mm shots, but the pilot managed at the

last moment to avoid crashing into the sea by veering upward from

his original aim at the ship’s waterline and crashed into

Whitehurst’s superstructure. The plane was a Val bomber, with a

500-pound delayed action bomb. It hit the port side of the ship,

went through the CIC Room (Command Information Center) and Pilot

House, both located on the deck between the Flying Bridge and the

Radio Room (my battle station).[1]

After passing completely through the CIC Room and

Pilot House, the plane came to rest on the starboard search light

platform (where the dead pilot was found in his cockpit the next

day). The bomb went through the ship and exploded in mid-air fifty

feet off the starboard bow, causing heavy casualties among those in

exposed battle stations on deck. All personnel in the CIC Room and

Pilot House were killed. The deck of the CIC Room (the overhead of

the Radio Room) was ripped open sending flaming gasoline into the

Radio Room.

Of the four of us in the Radio

Room, one was killed outright, one died from asphyxiation, and two

of us escaped with burns.

The official casualty list from the

attack was 37 dead or missing and 37 wounded – one-third of the

ship’s complement of about 210.[2]

Similar Attacks

The attached article in “Trim But

Deadly” describes two similar Kamikazi attacks, one on USS

Oberrender DE 344 and one on USS England DE 635. Both attacks took

place almost simultaneously, at 1853, on May 9, l945, twenty-seven

days after the attack on Whitehurst. All three ships were attacked

in similar circumstances.

note: England’s

experience was similar to the attack on Whitehurst, with the

Kamikazi striking from the starboard, not port, side. England's

casualty count was also 42. The plane similarly struck just below

the flying bridge followed by an explosion of the delayed action

500-pound bomb. Bowers strike was directly through the sonar shack.

A head on blow to the port side above the pilot house. The final

count of Bowers casualties was 65. Witter took a hit in the engine

room wit 13 casualties. mc

My Experience

Needless to say, I survived the

Kamikazi attack on Whitehurst, but, as I will explain later, Lady

Luck played her part again, or I would not have made it.

On this particular GQ, we soon knew

we were in the thick of some action, because shortly after we went

to GQ, Whitehurst began putting out substantial, though sporadic,

gunfire.

Suddenly the gunfire became much

greater. In almost no time it appeared that every gun on Whitehurst

was firing without let up. Although the four of us in the Radio

Room could not see the action, there was no question that Whitehurst

was being targeted by a Kamikazi at close quarters.

Then we were hit. The crash was

loud and violent. Metal wrenched. The ship was massively shaken.

We knew instantly what had happened. Fire was all about us. The

heat was immediate – like being thrust into an oven. My first

thought was “My God. So it happened to me. I’ll be just one more

sailor who died trapped in a closed compartment in a stricken ship –

but My God, it’s hot, it will be over quick. I won’t last long.”

These thoughts flicked into my mind in a millisecond.

But wait! Death was not going to

be instantaneous. There was some brief time to act. But do what?

The situation was apparent in a glance. Loften and Yeager sat

turned in their chairs, unhurt, not on fire, stunned, looking at

me. On the other side of me, Paul was propped up in a strange

upright position, impaled by the door of the Radio Room which had

been blown off its hinges and was holding him upright like part of

an A-frame made by him and the door, his head protruding through the

displaced louvers in the door’s upper panel. He was still. Parts of

his clothing were on fire.

But do what? The only escape was

out into the flaming passageway, turn aft, and go back and undog the

watertight door to the boat deck. I did not believe I would survive

in that flaming passageway long enough to undog that door. But not

to try would be to die without a struggle. What else to do in the

time left?

I looked at Loften and Yeager – I

remember trying to conjure up the best command voice I could muster

to indicate a degree of confidence – and said something like,

“C’mon, let’s go!” Or maybe, “C’mon, let’s get out of here.” It

was probably the former, because I think it was all I could choke

out.

All of this took no more than 10

seconds, if that. It bothered me not to attend to Paul, who was

there motionless. I had pangs of feeling about responsibility to

rescue him, but I knew it would be impossible if he were

unconscious. However useless it may have seemed, I stopped for a

swift moment and shook him, shouting in his ear. There was no

response, but that brief gesture helped my conscience.[3]

I darted into the passageway with

Loften and Yeager behind me and rushed aft with my eyes closed, arms

shielding my face, and headed back to the dogged-down door. I

hardly knew what I was doing. I could not see and was flailing

blindly. The heat was intense. The next thing I recall was

slipping and falling onto the coaming of the open door as someone

behind climbed over me to get out.

I scrambled over the coaming, went

a step or two starboard, and without any wasted movement, clambered

over the starboard rail of the boat deck and dropped into the

water.

I ended up deep in the water, and

it took a while to surface. But when I did, what a glorious

feeling! I had made it. Here I was afloat and alive on a bright

day, with fresh air, and cool seawater washing over me. What a

transformation!

But no sooner had the euphoria

struck than I was immediately sucked down under the water by a

powerful force. I was drawn down very deep, tumbling and twisting.

I thrashed and resisted, trying to get right side up, but it was

confusing. At long last, the water became less turbulent and I

managed to get headed upward, kicking and thrashing toward the

surface.

But I had been down a long time and

I was very deep. I struggled hard to get to the surface. It seemed

to take forever, and the thought crossed my mind, “My God – how

ridiculous to be saved and then die drowning.” For a long time I

thought I would not make it, but just as I felt I could hold out no

longer, I could tell I was nearing the surface. I finally broke

through and gulped air – a second great feeling of unbelievable

relief. I realized I had been in the wash of the propellers, and

now was out of it. The ordeal was over. Now I truly was saved!

I looked about for Whitehurst,

expecting to find it nearby, where I could be taken back aboard.

Somehow, I expected to find the ship stopped in the water, like an

automobile smashed into on a highway and no longer moving. As well

ordered as I believed my thought processes were in this crisis, I

realized the mind was playing tricks. The ship was off in the

distance, smoke pouring forth from her fires as she proceeded even

farther away.

Completely irrationally, it had

never occurred to me that I would be away from help after I went

into the water. Not that I would have done anything differently. I

had not even thought about the pros and cons of going overboard. I

was on fire, and the quickest way to quench fire was to get into the

water.[4]

But, like some fanciful dream, I expected everything would be back

to normal once I doused the fire. I would simply get back on the

ship. How strangely the mind can act.

When I looked about, I saw, perhaps

a hundred yards ahead of me, in the direction of the ship, two other

people in the water, so I started toward them.

As I did, I noticed something

strange about my hands. They had some stringy white material

clinging to them. I thought there must have been a sticky white

substance in the water that I had passed through. I tried

unsuccessfully to wipe the stuff away, but it clung tight. After a

few more attempts to get rid of the clinging substance, I came to

realize that the stuff was shreds of my skin.

Up to that moment, I had no

awareness of my burns. The sea was cool and felt good[5].

I had no sensation of being burned on my hands or anywhere. I felt

that my dive into the sea had put out the fire on my clothes and

that I had miraculously escaped without harm. But I now knew this

was not so. Certainly the skin on my hands had been damaged, with

shards of useless skin hanging there. Still, I felt no particular

discomfort.

Swimming toward the others, I felt

safe in the water. Before the war, I was not an experienced

swimmer, but after signing up for the Navy, I had taken a course on

survival swimming and how to tread water. At Harvard, I had once

tested myself to see how long I could swim, and after forty-five

minutes I knew I could swim almost indefinitely if necessary. I

regarded a calm sea as friendly, not threatening.

I saw other ships about. As I made

progress swimming toward the two others, I felt confident we would

be rescued,

Awaiting Rescue

When I reached the others, I found

they were Lieutenant Vincent Paul and an enlisted man, both from

Whitehurst. I knew Paul well, but was unacquainted with the

enlisted man. Paul was not hurt. As he greeted me, he suggested

that I inflate my life preserver. Up to then, I had been swimming

and had not even thought about the life preserver. Because my hands

were too damaged to squeeze the CO-2 cartridges, Paul did the

inflation. The life belt, of course, was a big help, since I was

fully clothed – underwear, T-shirt, long-sleeved khaki shirt,[6]

khaki pants, socks, shoes.

When I spoke to the enlisted man, I

learned that he was in considerable pain. He thought his leg might

be broken.

The three of us hardly talked.

Although the sea was not really rough, there was a good chop to it.

We put the backs of our heads to the direction of the wind and chop,

which was not only the best defensive posture for the choppy water

but also let us face in the direction where we might expect to see

any approaching rescue vessel. Despite the effort to protect

against the choppiness, I found I could not keep from swallowing

seawater as it washed over my head and down my face.[7]

I don’t recall any conversation

about where anyone of us was when the ship was hit. Such details

seemed unimportant. We all knew what had happened – and it was

difficult to talk with water shipping over our heads. We were

simply waiting to be rescued, as we felt we would be, and that was

enough to occupy us – or at least me, because, as we waited, I also

began to get quite cold. The water, which had seemed so refreshing

at first, was now chilling me.

Rescue

In about a half-hour, we saw a

camouflaged destroyer-type vessel (it was the USS Crosley APD 87, I

later learned) approaching us. It came near, slowed and launched a

boat. When the boat came to us, we were asked about any injuries.

The enlisted man with us in the water did not speak, but I remember

answering for him and suggesting that he be taken care of first

because his leg might be broken, so they pulled him into the boat

first.

I had been checking my watch and I

noted that we had been in the water forty-five minutes.[8]

My memory is fuzzy about how we

proceeded to get aboard our rescue vessel – whether I got aboard

under my own power, was lifted or helped aboard, or what. I do know

that I was cold and tired and welcomed being cared for by people who

seemed to know what they were doing. I was entirely willing to let

them take over for me and do what was necessary.

First Aid

I didn’t know where Paul and the

enlisted man with us were taken, but I was laid down on a table in

the crew’s general mess (eating) room. They gave me a shot of

morphine, which to me seemed unnecessary because I was not feeling

any great pain. I dismissed it as probably just standard

procedure. They also started cutting away my clothing, which again

seemed wasteful and more than necessary, but at that point, I was

not about to protest. They seemed quite experienced in what they

were doing.

I noticed that they were also

giving me blood plasma. This surprised me. I knew that wounded

soldiers in the field were given blood plasma to counteract the

shock effect of the trauma and that it was often a matter of life

and death to administer the plasma as soon as possible to avoid

death from the shock alone. So I asked if they thought I was

suffering from shock. Their answer was yes. They supplemented this

by saying that burns create shock and that in the case of injury

from burns, it is very important to give plasma to the victim.[9]

About this time, I needed to

urinate. Since I was under their control lying flat on my back on a

mess table, I asked them how I could go about it. I thought,

because they seemed to be medical people,[10]

they might have one of those gadgets used for this purpose with

bedridden males. To my surprise, they told me, “Just let it go.”

“Right here?” “Yeah, right here, just go ahead.” So I did. It

seemed strange, but I was too dim-witted to realize that it made

little difference, since the place was already dripping with

seawater from my clothes.

Their next step was to slather me

with Vaseline (petroleum jelly) wherever I was burned and then cover

those areas with layers of gauze. This meant putting bandages in

places on my legs, arms and back, and completely covering up my

hands and face with gauze wrapping. When they finished, I couldn’t

use my hands and couldn’t see.

During the course of all this, I

was talking with them and answering their questions, and they were

answering mine. They seemed dumbfounded when I told them I had been

in the radio room. They had seen the attack and did not think it

possible that anyone could have escaped from where I was. They

passed this information around to others who came by and all

expressed absolute amazement that anyone could have escaped from

there.

I learned that their ship was

Crosley APD 87, a DE converted to a small attack transport that

carried small groups of personnel for specialized landings – for

example, the transporting of Navy Seals (Underwater Demolition

Teams).

Transfer

The next step was to transfer me to a suitable

place. This turned out to be a transfer a few hours later to USS

Crescent City APA 21.[11]

– “about 1900” according to

notes I subsequently made in my

Navy file.[12]

I was transported in some kind of

small craft to Crescent City. I could not see or help myself with

my bandaged hands, so I did nothing but let whomever it was take

charge of me. Once we were at Crescent City, there was considerable

commotion around it and I recall it taking some time for anyone to

get to me. I was in one of those ridged wire stretchers and was

lifted aboard by some mechanism. Once aboard, I was laid in a bunk

located in what, from the sounds, seemed to be a small room with a

number of other wounded being taken care of. I was comfortable and

do not recall being in any pain. It was going into nightfall, so

the time for further kamikaze attacks had passed. I rested and

slept. The morphine may have had an effect

The next day, my main concern was

that I was helpless. I could not see and could not use my hands. I

could walk, although it hurt a bit when blood rushed into a bandaged

lower leg. I worried about how I could get out of that room if the

ship were hit. I knew the ship was not underway and was somewhere

off Okinawa, but not sure where.[13]

I therefore assumed it was as vulnerable to another kamikaze attack

as any other ship. I thought it might still be stationed off the

beach where it had landed troops.[14]

Attendants in the room were busy, but I managed to ask one of them

about my concern. He assured me someone would lead me if I needed

to get out. I knew of course that would be the intention, but I

wanted some assurance I would not be forgotten. I also knew it was

an intention that might not be able to be fulfilled.[15]

My Navy records show that I was

aboard Crescent City for the next four days. I don’t recall much

about those four days – all of which were spent in that bunk –

except for the day after my arrival. There was a radio in the room,

and during that next day an announcement came over it that President

Roosevelt had died.

This of course was major news, and

the attention given to it on the radio was not surprising. But it

gave me a strange feeling – all this attention to one man’s dying

when all about me I knew of carnage and death in wholesale numbers.

Each loss of a human life out here was just as tragic on a personal

level as the loss of any other human, and just as wasteful of one of

God’s wonderful creations. But obviously the life of a world leader

was something different and justified an enormous amount of

attention. I did not resent the attention, nor did I think it

should not be given. It just left me with a very strange feeling,

which even now comes over me as I write.

My stay aboard Crescent City for

the next three days was just a temporary holding action until I

could be transferred elsewhere. I received no further treatment,

nor did any seem necessary. My bandages remained in place. Time

just passed.

Hospital Ship and Homeward

On April 16, 1945, I was

transferred to the hospital ship, USS Hope AH 7, which after a few

days left for Saipan. By then my burns had been rebandaged and were

healing well. I was transferred to the Naval Hospital at Saipan on

April 22, 1945, and was evacuated by air on May 15, 1945. Arriving

at Hawaii on May 16, 1945, I was transferred to the Naval Hospital

at Aiea Heights. Later, in an outpatient status with burns healing

nicely, I visited with shipmates aboard Whitehurst. The ship was

under repair at the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard and, among other things,

was being outfitted with reels of electric cable in place of her

torpedo tubes, so she could use her steam-driven electric drive

generators to supply shore power when the invasion of Japan took

place.

From these visits, I learned for

the first time what had happened to the ship and to so many of my

shipmates on the day of the attack. I learned also of the

blown-away door to the boat deck that had allowed Yeager and me to

escape to safety.

I was detached from Aeia Heights

Naval Hospital on June 12, 1945 and provided transportation aboard

the U.S. Naval Unit S.S Matsonia to San Francisco, where I arrived

on June 17 and was transferred to the Naval Receiving Hospital in

San Francisco.

Unfortunately, my hospitalization

was not over, because I came down with Hepatitis B from the blood

plasma given me on the day of the attack. So on July 3,1945 I was

transferred from the Receiving Hospital to The Naval Hospital at

Oakland (Oak Knoll). I was not discharged from treatment at Oak Knoll until August 29, 1945. By then, Japan had surrendered. World War II was over.

[1]

Being closed up in the Radio Room, I did not witness the

attack. The details recounted here are from the Whitehurst’s

official battle report and from conversations with shipmates.

[2]The

37 wounded figure is taken from published Navy reports.

However, on April 13, the day after the attack, J. C. Horton,

the commanding officer of Whitehurst reported in a letter to the

commander of the task group in which Whitehurst was serving the

name, rank, and serial number of the casualties. He listed 31

dead, 6 missing, 22 wounded (as the only wounded officer, I

headed the list) and 5 “Death[s] on board hospital ship to

date.” A copy of that letter is in my Navy file.

[3]

My conscience was even more relieved when I learned from

shipmates months later that Paul had died instantly of a broken

neck, undoubtedly caused by the Radio Room door slamming into

him. He was found with his head grotesquely sloshing back and

forth as he lay on the deck of the Radio Room in water

accumulated from the fire fighting.

[4]

Subconsciously, I am sure I was

influenced to go overboard by the feeling that I was in safe

waters, not far from that small island group now in our control,

Kerama Retto, which I looked at daily as we patrolled back and

forth off its shore only a mile or so away. I remember feeling

somewhat assured by this proximity and the thought that it might

even be possible to swim ashore, if it were ever necessary. Had

Whitehurst been operating alone far at sea, my subconscious

decision, I’m sure, would have been to suffer onboard.

[5]

Whitehurst took daily readings of sea temperature. At Okinawa,

the readings were about 72 degrees.

[6]

For flash burn protection, all

Navy personnel were under orders to wear long-sleeved shirts

rolled down to the wrists. The fact that my hands turned out to

be burned worse than my arms shows the wisdom of this rule.

[7]

Since the wind and chop were

coming from the direction of Kerama Retto, this buffeting action

by an otherwise calm sea made me realize how impossible it would

have been for me to swim to one of those seemingly close islands

and the false comfort I had taken in thinking that I might be

able to. (See footnote 4.)

[8]

I had been keeping track of the

elapsed time in the water and have remembered it ever since, but

I was not particularly noting the time of day. Months later,

before I knew the actual time of the attack, I made a

handwritten entry in my Navy file giving the time we were picked

up by Crosley as “about 1530.” It was years later before I knew

the actual time of the attack.. The Navy’s “Secret Action

Report” of the attack, now declassified, states that Whitehurst

“Sounded general quarters and all hands manned battle stations”

at 1433 and that the “approximate” time the plane crashed the

ship was 1502. By this estimate, my handwritten note was only

fifteen minutes off.

[9]

The reason burns can lead to

shock, I subsequently learned, is that substantial body fluid

(blood plasma) can ooze out through the burns.

[10]

I was probably in the hands of a

pharmacist’s mate (the navy term for what the army would call a

medical corpsman). Small ships, such as DE’s did not have

doctors, but had petty officers with a pharmacist’s mate

rating. All these petty officers, of course, had Navy training

for their duties, but they came from various civilian

backgrounds. Aboard the Whitehurst, we found it amusing that

our pharmacist’s mate had been an undertaker in his civilian

life.

[11]

An APA was a large attack transport used to bring troops to land

on enemy territory. There were about 250 of them commissioned

in World War II. According to her ship’s history, Crescent City

had been converted to a temporary hospital evacuation ship in

March and had arrived at Kerama Retto on April 6, “[r]eceiving

casualties from the beaches of Okinawa and from other

ships….[She] remained at Okinawa receiving casualties and other

transients until the end of the war.”

[12]

I entered these notes months later

on the Navy’s paper work, which followed me. My Navy file shows

that I received orders dated that very day of April 12

(undoubtedly delivered to the Medical Officer of Crescent City

without my intervention)

signed by Whitehurst’s

commanding officer, J. C.

Horton, reading as follows:

“You are

hereby detached from all duties assigned you aboard this ship;

will report to the Medical Officer, USS. CRESCENT CITY (APA-21)

for medical treatment…Diagnosis as follows: # 2508 – Burns,

Extremities/Key Letter “K”

[Enclosed

were my Navy Pay Record (so I could get paid), my Health Record,

and my Officer’s Qualification Jacket]

[13]

Upon writing these memoirs, and

researching the history of Crescent City, I learned that the

ship was anchored in Kerama Retto, a relatively safe place to

be, because it was ringed with small mountainous islands, making

kamikaze approaches difficult. In addition it always had a

concentration of ships there, which could bring some awesome

firepower to bear on a kamikaze attack.

[14]

Again, it was not until doing

research for these memoirs that I learned that this particular

APA ship was no longer an attack transport, but had been

converted to a hospital evacuation ship.

[15]

My concern would not have been so

intense if I had known that this APA was not serving as an

attack transport. As an attack transport, which I thought it

was, I regarded my presence there as something unusual, where I

could easily be overlooked in an emergency involving their

regular duties. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Excerpt from p. 491, "United States Destroyer Operations in World War II" By Theodore Roscoe, US, Naval Institute, 1953 Contributed by Roger Ekman, Capt USN. Ret, who served on Whitehurst In the action on the afternoon of April 12th, destroyer escort Whitehurst (Lt J. C. Horton, U.S.N.R. Commanding) was maimed by a small, but vicious bomb and a smash from a suicidal "Val." The plane plunged into the CIC. and the ship's entire bridge superstructure was enveloped in flames. All hands in CIC. and pilot house were killed. All in the radio room, on the deck below, and at most of the forward gun mounts were killed or badly wounded. Although this was a baptism of fire for captain and crew, the Whitehurst men fought conflagration, battle damage, and successive Kamikaze attacks with a veteran skill and discipline that saved the DE.

|

|

WWII

Era | Korea War &

'50s | Viet Nam & 60s |

Reunions |

All Links Page

Search & Rescue

Memorial | Poetry | Enemy Below | Taps List | Photos/Armament | History | Crews Index | Home