|

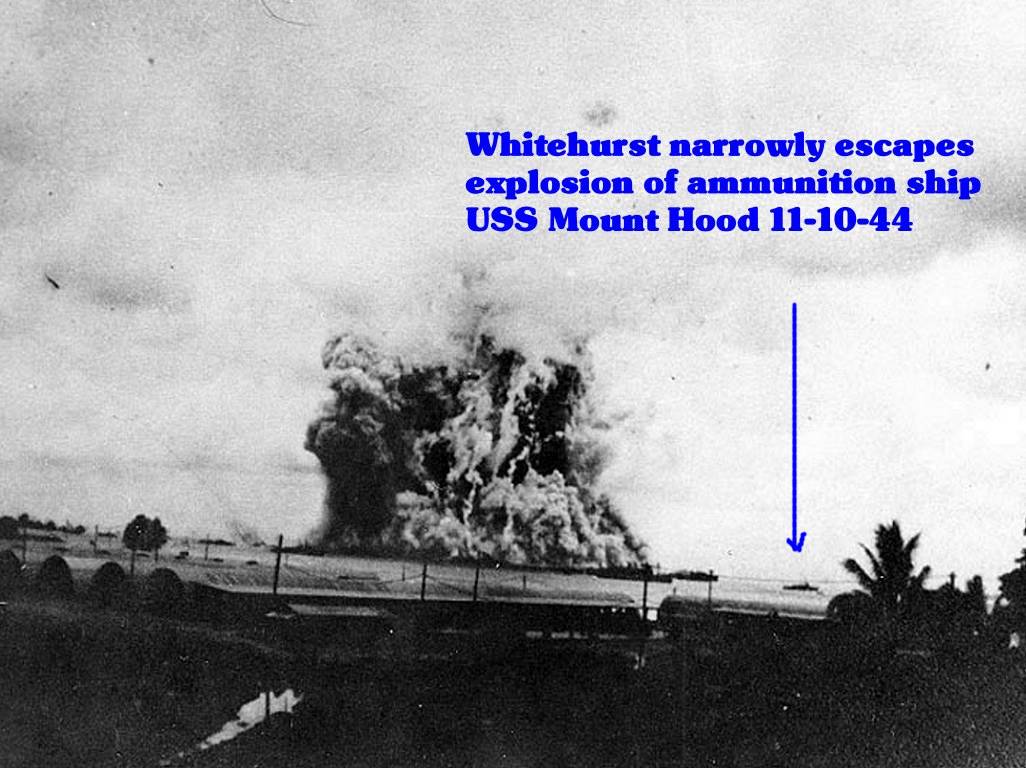

EXPLOSION OF AMMUNITION SHIP, MOUNT HOOD, |

|

|

AT MANUS HARBOR NOVEMBER 10, 1944 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ensign Fred Mielke |

Fred Mielke ca 2001 |

|

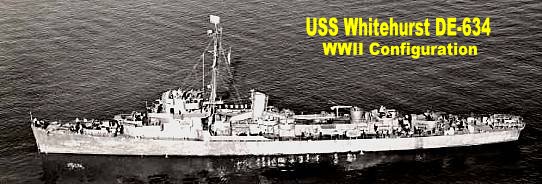

The attached article in “Trim But Deadly” about the explosion of the ammunition ship Mount Hood, AE-11, and the stories in the article about Kamikazi attacks on two destroyer escorts, USS Oberrender, DE 344, and USS England DE, 635, have triggered me to write a few memoirs of my own – particularly including my experiences aboard the USS Whitehurst, DE 634, as supply and disbursing officer from November 10, 1944, (the date of the explosion of Mount Hood) to April 12, 1945 (the date Whitehurst was hit by a kamikaze, – and the same date President Roosevelt died).

I have recounted

some of these experiences to family and friends over the intervening

years, but I will not be here forever, and if anyone is interested

later on, this writing will at least be authoritative and not

subject to vague memory. These happenings are still well imbedded

in my memory. After many weeks of island hopping across the South Pacific to find my ship, with periodic long waits for available Navy transportation, I reached Manus Island, a small island in the Admiralty Islands, north of New Guinea, just below the equator. I checked into the receiving station, found that Whitehurst was not in port and began waiting again. Unlike the other places I’d come from in the South Pacific, Manus was being developed as a major advance naval base in the push toward Japan. It had a large deep anchorage (Seeadler Harbor), fifteen miles long and four wide) protected by a coral reef. Adjacent, at its eastern tip, was Los Negros Island with ample space for an airstrip. Manus was alive with activity, both onshore and offshore. Every day coral was being blasted out of the harbor, scooped into trucks, and hauled away as paving for roadways being built. There were many ships coming, going, and at anchor, and there were substantial shore installations. While there, I ran into a number of friends whose ships were in. We’d visit in the Officers Club and occasionally I’d visit one of them aboard his ship. After 25 days of waiting, I received word that Whitehurst had come into port. November 10, 1944 It was about 0700 November 10 when I was told that Whitehurst was in port. The message was that Whitehurst would be leaving right away, and that I had 30 minutes to pack my gear, get a jeep ride to the dock, and board the ship’s motor whaleboat. Needless to say I scurried, anxious to finally get aboard Whitehurst. I was at the dock in time. The coxswain and I scrambled into the whaleboat with my gear and we went full speed out to Whitehurst, at anchor in the bay. By the time we got to the ship, it had already weighed anchor and was underway at slow speed, heading toward the harbor opening. We moved alongside it, allowing me to climb onto a ladder dropped down from the quarterdeck for me. The coxswain took the whaleboat forward to be hauled aboard to the boat deck, my gear included. I went up the ladder, requested permission to come aboard in accordance with Navy protocol, and carried out my orders by reporting to the commanding officer, Lieutenant J. C. Horton, captain of the ship. He was on the flying bridge, in control as the ship headed toward the harbor channel and open sea. The captain welcomed me aboard, apologized for crowded conditions that would necessitate my being bunked in the unoccupied ship’s brig, introduced me to one or more nearby officers, and had one of them, Lieutenant Jim Nance, arrange to get me settled. This episode took but a few moments. Nance and I departed the bridge and went to the wardroom, where he showed me the officers quarters, including the shower and head, and his stateroom, which he suggested I use for dressing, shaving, etc. while I was quartered in the brig (which had nothing more than two over-and-under bunks in it). He left me as I put some water in the basin and prepared to shave. This second episode, similarly, took only another few minutes. We were still in calm water inside the harbor. Just as I was about to start shaving, there was a sharp scrunching sound as though the ship had run aground on coral. I was startled and thought that we must have missed the channel and scraped onto coral. I could imagine nothing else, although the ship did not seem to shudder or lurch. Racing out on deck, I immediately saw a huge, roiling mushroom-shaped cloud rising rapidly into the sky. It looked awesome. It was a monstrous force moving swiftly and powerfully, rising high into the sky. As it moved upward, it displaced and shoved aside a great mass of clouds. The whole sky was turmoil of movement. There was no question that it was an explosion. Others aboard knew immediately that it was the explosion of an ammunition ship that had been at anchor in the same part of the Bay where Whitehurst had been anchored, and that Whitehurst had just passed by on its way to the harbor entrance. Lew Cowden, a machinist mate aboard Whitehurst, remembers the event as follows: “We were taking on supplies and got word to hurry, the convoy was waiting on us. We started to head out while still unloading the last of the supplies. The “all hands” work party had been secured, and we headed toward the open sea where the convoy was forming, when it exploded. They tell me we were much closer when taking on supplies and went right past her on our way out. I [had] just started up the ladder to the fantail when the blast pushed me back. I ran to the forward ladder and came up on deck amidships and saw the sight…I was told that we were far enough away to avoid damage from the blast and near enough that major debris blew over us.” Another description of the event appears in an unofficial log of Whitehurst kept surreptitiously by George Baskin, a metalsmith. His log, for that day reads as follows:

“Arrived at Manus Island at 0600. Left at 0730 convoying 4 LSTs and 16 LCIs. On leaving, we went right past the ammunition ship, Mount Hood, that blew up. If it had happened 3 minutes earlier, everyone topside on the Whitehurst would have been killed. We were about 5000 yards from it when she exploded. I thought my ear drums were busted. Guess God is with us.”

All of us aboard Whitehurst have speculated what would have been our fate if our departure from Manus that day had been delayed and Whitehurst were broadside to Mount Hood at 0803, the time of the explosion. As it was, I reported aboard perhaps ten or fifteen minutes before the explosion, at a time when the ship was moving slowly enough to allow me to jump aboard the gangway landing and the motor whaleboat to be hoisted aboard by the davits onto the boat deck. After that, the ship probably would have proceeded faster. If at that point she began making 10 knots (11.15 miles per hour) – a not unusual speed if she were headed for open sea and a waiting convoy – and continued at that speed for the next fifteen minutes, she would have added 2.88 miles of distance from the spot where I boarded her. This is remarkably close to the 5000-yard figure (2.84 miles) in Baskin’s log as the distance from the explosion. It is not hard to imagine, therefore, that Whitehurst was indeed just about passing Mount Hood when I came aboard. What if I had been five or ten minutes late in reporting aboard, and delayed the ship from picking up speed to get out of the harbor? Suffice it to say that Lady Luck (or God, as Baskin puts it) was with us that day. For me it was the first of a series of lucky strokes. The others all occurred on April 12, 1945, when Whitehurst was struck by a Kamikazi. |

|

|

|

|

WWII

Era | Korea War &

'50s | Viet Nam & 60s |

Reunions |

All Links Page

Search & Rescue

Memorial | Poetry | Enemy Below | Taps List | Photos/Armament | History | Crews Index | Home